Mastering Pure Functions in TypeScript

In the world of software development, particularly when moving towards functional programming patterns, few concepts are as high-leverage as the Pure Function. It sounds academic, but the practical benefits—easier debugging, bulletproof testing, and predictable behavior—are immediate.

What is a pure function?

A function is considered "pure" if it adheres strictly to two rules:

- Determinism: Given the same input, it will always return the same output.

- No Side Effects: It does not modify any state outside its scope or interact with the outside world (e.g., no API calls, no DOM manipulation).

Rule 1: Determinism

For a function to be pure, it cannot depend on hidden values like time, random numbers, or database content.

Impure Example

This function is impure because it depends on Date.now(). If you run this twice with the same argument, you get different results.

const createUser = (name: string) => ({

id: Date.now(), // ⚠️ Hidden dependency on time

name: name,

});Pure Example

To make it pure, we move the dependency into the arguments. Now the output is strictly tied to the inputs.

type User = {

id: number;

name: string;

};

const createUser = (id: number, name: string): User => ({

id,

name

});Rule 2: No Side Effects

A side effect occurs when a function changes something other than its return value. In TypeScript, objects and arrays are passed by reference, making it easy to accidentally cause side effects via mutation.

Impure Example (Mutation)

const cart = [{ item: "Apple", price: 1.2 }];

const addToCart = (currentCart: any[], newItem: any) => {

currentCart.push(newItem); // ⚠️ Mutates the original array

return currentCart; // return is needed here because push() returns length

};Pure Example (Immutability)

Instead of modifying the input, we return a new version of the data. Using readonly helps us enforce this.

type CartItem = {

item: string;

price: number;

};

const addToCart = (

currentCart: readonly CartItem[],

newItem: CartItem

): CartItem[] => [...currentCart, newItem]; // ✅ Returns a new arrayThe Sandwich Architecture

You cannot build a useful app with 100% pure functions. You need to save to databases and call APIs. The goal is to isolate your logic.

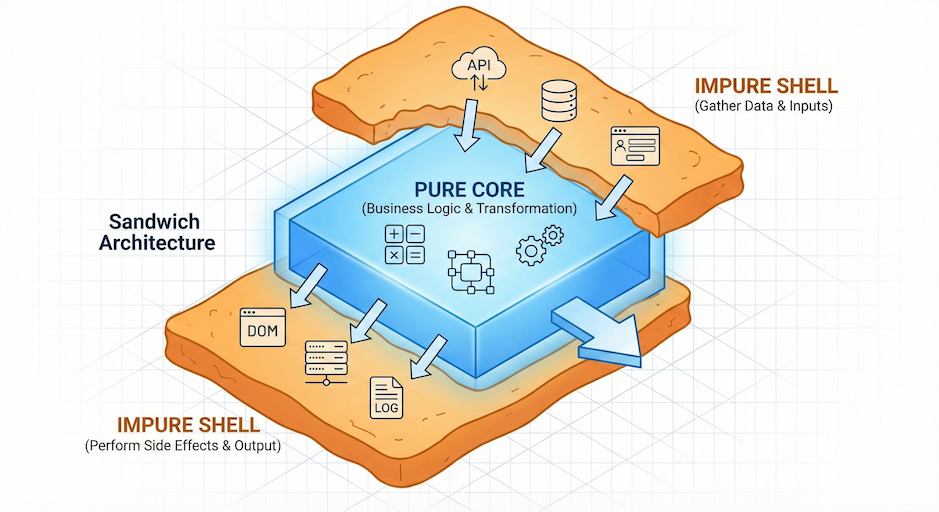

The Sandwich Architecture: Pure Core wrapped in an Impure Shell.

- Impure Shell (Top): Gather data from the outside world (API, DB, User Input).

- Pure Core (Middle): Perform business logic, calculations, and transformations.

- Impure Shell (Bottom): Perform side effects with the results (Update DOM, Save to File).

Summary

Pure functions make your TypeScript code easier to test, move, and reason about.

- Predictability: Same input always equals same output.

- Testability: No mocks required for pure logic.

- Refactoring: Pure functions are decoupled from the environment, making them easy to move around.